Rocket Ships & Race Cars: The Dangers of Anchoring on Incomplete Data

We need to question the initial trust we have in data. Just because it’s thrown up on a slide, or sent over in an email, doesn’t mean that it’s right or complete. Sometimes it can even be dangerous.

Intro: Beware the Data

One of the things unintentionally we’re taught in school is to trust the completeness of data that the teacher throws up on the PowerPoint slide or hands out printed on a piece of paper. From the time we are young (starting in elementary school) it is implied & reinforced that you can implicitly trust the information given to you from someone like a teacher, a boss, a newspaper, etc. We usually don't bother to fact check the data before diving into our calculations, analysis, or project work because (A) we trust the source, and (B) we are eager to "get started" on the work. Something we do even less is to ask "is this all the data that exists / that we have access to?"

Unfortunately, that mindset can have tragic consequences as a group of Harvard MBA students learned (as told in a fascinating story from the New York Times best-selling book “Range” (summarized below).

We need to question the initial trust we have in data. Just because it’s thrown up on a slide, or sent over in an email, doesn’t mean that it’s right or complete. Sometimes it can even be dangerous. Here's a throwback article from Jason + Austin on how to think more critically about data, no matter where it comes from

“What if everyone just agrees? I say, race this thang!”

That quote, uttered by a Harvard MBA student, was captured by David Epstein, author of the book “Range”, who once spent an afternoon with a group of 7 HBS students vigorously debating one of the most (in)famous business school case studies ever created: “Carter Racing”.

The crux of the case is whether the fictional Carter Racing team’s Formula 1 car should compete in the biggest race of the season. Each HBS team is presented with a short packet that contains a confusing mix of data and background info: weather patterns, history of failures on prior Carter racing cars, financial pressures, opinions from the racing team’s mechanics & engineers, etc…

It’s a lot to sort through, especially since each team has to make a Race vs. No-Race decision in < 1 hour.

The Carter Racing case generally divides students into two distinct camps, those who want to race and those who don’t.

The argument in favor of racing:

Thanks to a custom turbocharger, Carter Racing has placed in the top 5 in half of the last 24 races.

Due to its success, Carter Racing has received a lucrative oil company sponsorship AND stands to receive up to $2M in another sponsorship from a tire company as long as it finishes in the top 5 in this last race.

If Carter Racing chooses not to race and withdraws, it would lose part of its entry fee and may never get another shot at more sponsorship $$$.

The case against racing:

In 7 of the last 24 races the engine failed, damaging the car. The mechanics aren’t sure what has been causing the problem.

If the engine fails on national TV, the team will lose their current oil sponsorships, can kiss the $2M tire sponsorship goodbye, and perhaps be out of business.

Messy Data = Complicated Opinions

To make matters even more complicated there are more data points for the HBS students to wade through, that don’t necessarily favor either argument:

The race day is scheduled for a very cold day (colder than any other prior races)

Pat (the fictional engine mechanic) has no engineering training but has a decade of race experience. He thinks that temperature could be an issue. His evidence: when the turbocharger warms up on a cool day, engine component might change in size, causing failures

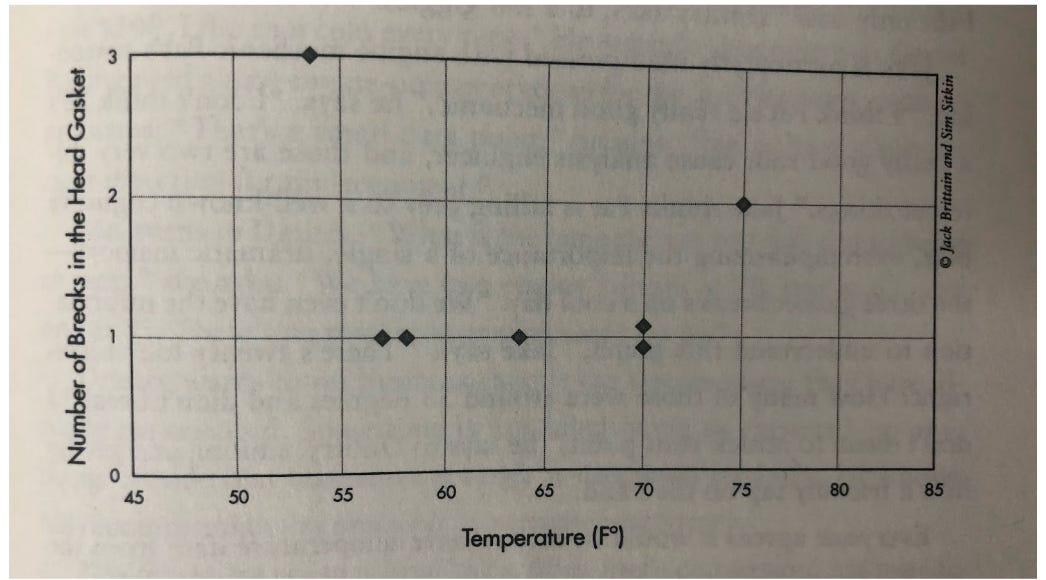

However, temperature data from the last 7 races shows no correlation between engine failures and temperature. Failures happened on both warm AND cold days (see graph below)

The First Engine Failure vs. Temperature Graph

The student debates described by David Epstein are fascinating. Everyone’s opinions are all over the map with regards to what data to value over another.

What Happened in the Harvard Classroom…

Just as it seems that the group will finish where they started (voting not to race) another student changes her mind after looking at her calculations. She decides that Carter Racing needs just a 26% chance of finishing in the top 5 to make it worthwhile. Once this student switches sides, it’s 4 votes to 3. They’re racing.

As they pack up their bags and head to the classroom, one student remarked aloud “This is just about money, right? We’re not going to kill anyone if we race, are we?” Everyone laughs.

When the students arrive in class the next day, they learn that most student groups around the world who have ever been assigned the Carter Racing case chose to race.The professor then goes around the room testing each team’s logic for racing or withdrawing.

Students had all sorts of approaches. Logic-trees. Probability calculations. Gut feeling. Most think the temperature data is a red herring (something intended to be misleading or distracting). One team even voted 7-0 in favor of racing because “if we want to make something of ourselves in the business of racing, this is the kind of risk we need to take.”

Finally the professor drops the big surprise. “Here’s a quantitative question for you all. How many times did I say yesterday if you want additional information let me know?” the professor asks.

Gasps spread across the room.

“Four times” the professor answers himself. “But not one of you asked for the missing data”. The professor then walks up with a flourish to the board and puts up a new graph, this time, with every prior race (including those that had no problems) plotted.

The Second Engine Failure vs. Temperature Graph

The new (and now complete) data shows that every single race below 65 degrees had an engine failure. Running a simple regression test shows the students that there is a 99.4% probability of engine failure on this final (very cold) race day.

“Does anyone else want to race?” the professor asks. This time, no one raises their hands.

The Gut Punch

The most troubling aspect of Carter Racing is that this case study isn’t actually about race cars.

The temperature and engine failure data are taken exactly from NASA’s tragic January 28th, 1986 decision to launch the space shuttle Challenger, with the details placed in the context of racing rather than space exploration. Even the characters in the case (such as Pat the mechanic) were based on real-life engineers at NASA.

Rather than a broken engine, Challenger had failed O-rings (the rubber strips that seal joints along the outer wall of the rocket boosters). Cool temperatures on launch day caused the O-rings to harden, making them less effective, and the case of Challenger, fatal. When the O-rings failed to properly seal a joint in the wall of a rocket booster, the Challenger exploded only 73 seconds into its mission. All 7 crew members were killed.

Tragically, no one at NASA felt that they should ask about all the other data points on launch days to see if temperature really would be an issue or not.

Don’t Trust the PowerPoint Slides

It was eerie how similarly Harvard Students came to the same conclusions as NASA’s ill-fated Challenger engineers. Like the NASA engineers, not a single student asked for the 17 data points for which there had been no problems. Obviously that data existed, but no one thought to ask for it. And their failure to ask “what other data do we need to make the right decision” turned out to be a fatal one.

Why does this happen? In a classroom, the teacher typically gives the material we’re supposed to have to complete the test or assignment. But in the real world, it’s often the case that we just end up using the data from whatever PowerPoint slides people put in front of us. Just like we were trained to do when we were students.

We need to question that initial trust we have in data. Just because it’s thrown up on a slide, or sent over in an email, doesn’t mean that it’s right or complete. We don’t usually do a good job of asking “is this the data that we want to make the decision we need to make?”. But that’s exactly what we should be asking.

Push back. Never assume that the data being shown is all you need to make a big decision. Ask for what else is out there. It may not always be a matter of life and death (like Carter Racing / The Challenger were), but in instances of high stakes, it’s always worth asking that question “what data do we really need to make this decision & how can we get it?”.

You’ll be grateful you asked.

Note: A big thanks to David Epstein’s book “Range” (chapter 11 in particular) for inspiring this article. We highly recommend this book to anyone interested in developing better decision making processes.