How a Simple 2X2 Matrix Saved the World’s Most Valuable Company

Why doing less is often doing more

“What would I do? I’d shut it down and give the money back to the shareholders”

That was the blunt and bleak answer Michael Dell (legendary founder & CEO of Dell Technologies) gave to a reporter on Oct 6, 1997 when asked what he would do to solve Apple’s then seemingly insurmountable problems.

27 years later, his answer seems laughable. Today Apple has a market cap of ~3 Trillion (Top 3 in the world) and seems to dominate every aspect of the global technology space. It is perhaps the world’s single most famous brand.

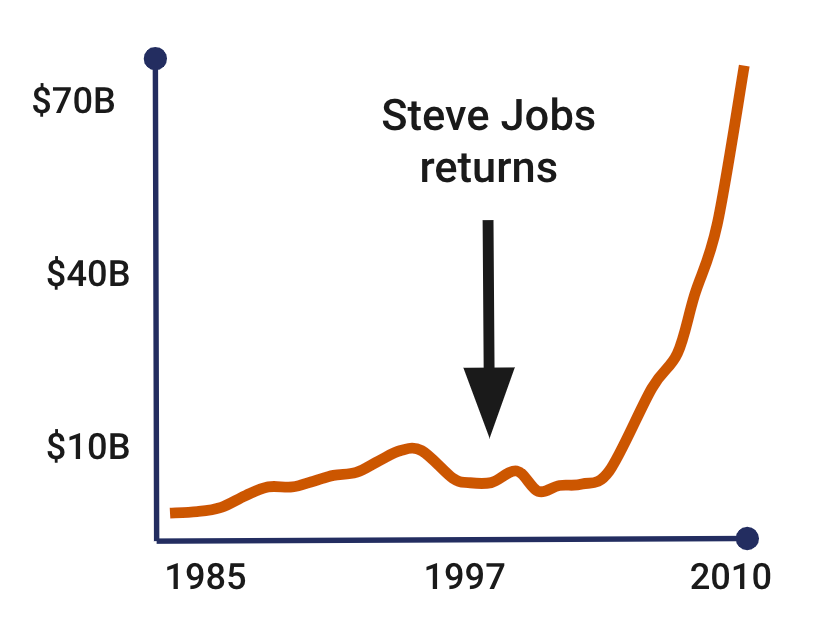

But in 1997, Michael Dell was simply part of the majority. Most people didn’t think Apple’s chances of survival were great. After Steve Jobs was pushed out of Apple in 1985, the company seemed to be caught in a nightmare of its own making. The new leadership had created a confusing array of over 70+ products and services, none of which were selling well. Sales had stagnated, cash burn was high, and morale (both employee and investor) was hitting rock bottom. Rivals Microsoft and Dell were surging, Apple was dying, and everyone knew it.

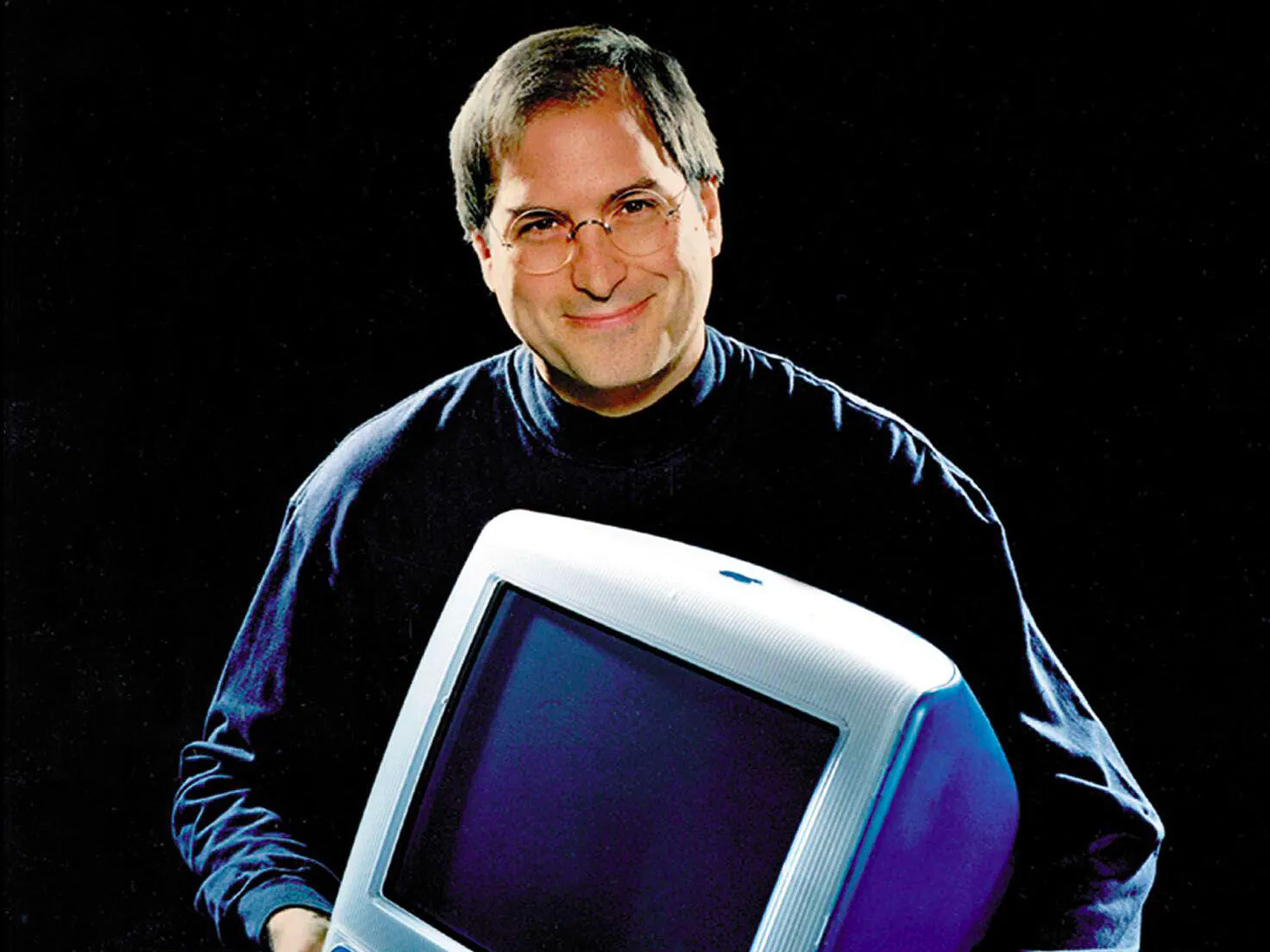

Out of desperation, Apple’s Board brought Steve Jobs back as CEO. A few months later, in September 1997, something happened that many regard as the turning point in Apple’s history.

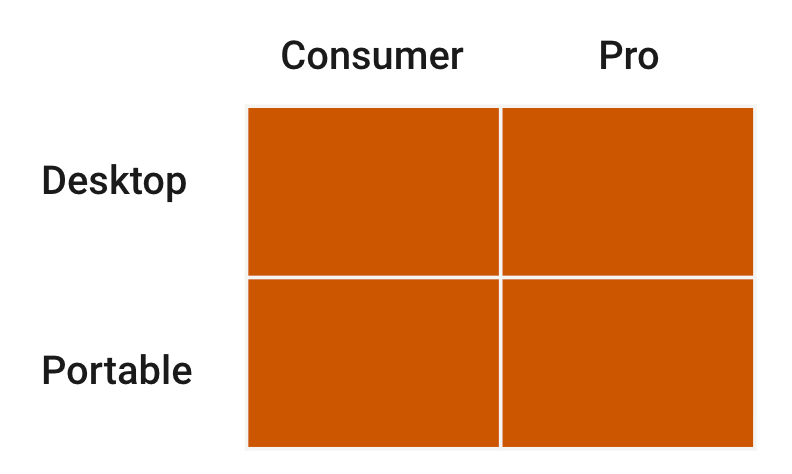

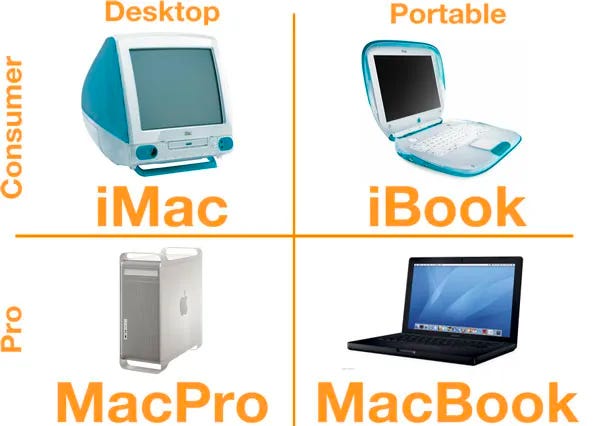

Steve Jobs walked up onto the stage at Apple’s Annual Developer Conference, took a marker, and drew up a simple 2X2 matrix with the top columns labeled “Desktop” and “Portable” and the other side labeled “Consumer” and “Pro.”

He then announced that starting that very day, Apple would only make these 4 products, and that all of the other 70+ products/services were being shut down immediately. No one was to work on anything other than these 4.

People at Apple soon found out that Jobs was deadly serious about this radical focus. Product Managers and Execs who didn’t get in line with the new approach quickly found themselves in hot water. Jobs would (in)famously even go so far as to berate and scream at anyone who didn’t quickly kill pet projects that didn’t fit into one of the 4 new products. You got onboard or found yourself shown the door.

What’s remarkable is what happened in the few years following. Just take a look at Apple’s sales growth chart.

Why such phenomenal growth? It turns out that extreme focus/simplicity has some enormous strategic benefits:

Because Apple only had 4 products, they could put their “A-Team” on every single one of them. Their top engineers, marketers, and designers could have legitimate input into each one of Apple’s product lines (something that had been impossible when there were simply too many products to cover and the “A-Team” was spread too thin)

With only 4 products Apple could be working on the next generation of each one while they were still introducing the first generation. This allowed their dev teams to always stay “1-2 steps ahead” of what the customer wanted and create a stream of timely, yet constant innovations.

The focus on only 4 products created a much simpler (and more efficient) supply chain, which meant they could turn inventory every 9 months instead of every 18 which dramatically improved cost savings up and down the value chain

The 2X2 strategy ultimately yielded 2 major winners: The iMac, and to a lesser extent (at the time), the MacBook Pro. These were “cash cow” products that provided the capital Apple desperately needed to invest in the next wave of growth and allowed it to take a firm spot as the market leader in the PC space.

Lastly, because Apple had killed 70+ different programs, they had freed up resources to start searching for the next “$100M idea”. While the rest of the company focused on the “core 4”, Apple identified a few select teams to deeply research the market and figure out what customers wanted next. The insights discovered by these small innovation strike teams led to the invention of the iPod + iTunes (the next major Apple products) which fueled growth in the early 2000’s.

The moral of the story

There are a lot of things to take from this, but I want to focus on just one: Strategy is just as much about what you decide not to do, as it is what you decide to do.

One of the things I notice most when I do consulting work or chat with folks considering their next career move is how often people and organizations never want to say no to anything. There is an immense fear of limiting one's options. As humans, we are hardwired to have FOMO (fear of missing out) when it comes to decisions, and so end up refusing to say “no” to anything lest we close a door that could potentially have a great prize behind it.

Some common examples I see often:

Business leaders who greenlight every project that comes across their desk saying “It all has to get done. Each of these things is critical to the company’s success!”

MBA or undergrad students who call me for career advice and say with a straight face that they are equally considering “working at F500 company, joining a consulting firm, or maybe joining an early stage startup” (as if all of these were very similar options and could somehow be pursued effectively simultaneously).

Companies that build products that are “jack of all trades but masters of none” (aka, the product does “everything”, but nothing particularly well)

People who have “to-do lists” that are a million miles long (I’m guilty of this often myself) and are convinced that they’ll certainly have time to do it all.

The problem with this strategy is that by refusing to say “no”, we unintentionally say “yes” to many things which don’t have that much value and end up spreading ourselves think (like butter over too much bread)

One of the things that separates a true “Strategy” from a “Plan” is that strategy is all about choices. It is a series of intentional tradeoffs that you make because you believe that some things are worth more than others. It is essentially making a series of well-informed bets because you believe the reward will outweigh the risk.

Someone who tries to place their bets on every area of the table actually has a poor strategy. Because they refuse to commit to any one area, they end up struggling across the board because there aren’t sufficient energy, effort, or resources behind any single one of their “bets”. As a result, they can’t get momentum (just like Apple discovered by spreading itself thin across 70+ areas before Jobs returned). The Index fund approach is an excellent method for achieving financial independence, but it’s not a great tool for achieving personal or organizational productivity.

Steve Jobs put it this way:

“People think focus means saying yes to the thing you've got to focus on. But that's not what it means at all. It means saying no to the hundred other good ideas that there are. You have to pick carefully. I'm actually as proud of the things we haven't done as the things I have done. Innovation is saying no to 1,000 things.”

The Challenge

One of my favorite things to do is to take a strategy principle and apply it to my personal situation. I’d encourage you to do the same. A few questions that may be helpful:

How can you apply this to your personal life? (are you trying to do your version of 70+ product lines? If you only had to pick 4 things on your to-do list to focus on, which ones would make the greatest difference?)

How can you apply this to your team at work? (which few projects would make the greatest impact in your team’s effectiveness? Remember that 80% of the results usually stems from 20% of the inputs)

How can you apply this to your company? (What should your business do to simplify? If you were CEO and had to choose only 1-2 things the company could do, what would they be?)

As Greg McKeown (author of NYT Best Seller “Essentialism”) once put it:

“How can you do ‘less but better?’”